Ross G Caldwell

Hi Michael,

(it's late for me, as you know, but hell it's Friday night... I'll do my best)

No, but approach my initial statement both literally and charitably. I said "if read", not "must be read". We're reading the images from roughly the same vantage point, so I assume we're sharing impressions rather than imparting dogma.

[/QUOTE]

Or should we accept, as we do with most works, that it is not a 20,000 word treatise by a Scholastic theologian but a work of art, and that some things are taken for granted?[/QUOTE]

A lot of things can be taken for granted. I think we're just learning what they might have been. Wegener was probably the first to write down that a Wheel of Fortune was implied in the arrangement of the vignettes above Fame. Can you assume, with full confidence, that it was the obvious interpretation to everyone in 1490?

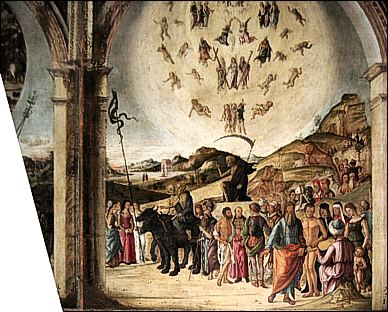

On "paper" it looks good, and your presentation is convincing. But I haven't stood there, where it would really make a difference. Maybe the average viewer doesn't get to see much of that, and instead has to make due with the bald Triumphs, and the suggestion of mysterious things in the heavens. Even more important than the content was the use of the image. The Triumphs were the primary meaning of the images - they are the closest to the viewer.

I don't know the layout of the chapel so I'm not even sure if the left-right dichotomy works - it could be that you walk into the chapel and see Death first, then Fame. You don't stand eye-level to both and read them as a text. If you *must* pass by Death first, then Fame, then this kind of reading breaks down. It could be that they are not meant to be read the way you are reading them - they might be "stand alone" triumphs, each self-sufficient.

[/QUOTE]

Yes, there are other things that could have been included, as always, including a hellmouth or whatever it is that would satisfy you. Yes, if you were creating a similar work then you would no doubt do it differently.[/QUOTE]

I sure didn't say that. I don't even know how to conceive, in this context, of "creating a similar work". I don't much about it, including the conditions of the commission.

"Insisting"? I think you're fighting shadows here, or at least misreading (deliberately?) me. I certainly never meant to imply that *I* believed in such an interpretation, and nowhere have I insisted on it. Talk about seizing on a stray (and hoping to be somewhat funny) remark. I'll be wiser in future and keep my erudite humor to myself.

Well, that was fun. I never thought of all that heresy. Let's see what else there is to get to.

Okay, but I imagine our 15th century readers considered it a unified work. Do you know differently? At least, all those cassoni and illustrated versions do have all six triumphs, even when they choose to emphasize some and neglect others.

I'm not really sure I understand what you're saying here. The world didn't go from medieval to "Renaissance" in 1450 (or whenever). Humanism was a multifaceted movement. There weren't many who would elevate worldly Man to the status of God. Even the most infamous humanist Prince, Sigismondo Malatesta, is shown kneeling before his namesake St. Sigismondo in his chapel in Rimini. He doesn't give himself a halo.

But... yeah, I think that the medieval Christian contemptu mundi still persisted pretty strongly, and that it's not a case of either/or.

It's obviously a celebration of Fame. For heaven's sake, look at the occasion - the birth of the first son. You want a Triumph of Death or some kind of contemptu mundi imagery, even a Wheel of Fortune, there?

This image is fully within the traditions of the society that produced it, and was immersed in the tragedy of history. If you look at other birth trays, they always have stories of great deeds and heroes (I just looked, a nice one of David and Goliath, with no contemptu mundi - definitely a humanist triumph).

We have to agree on the definition of Fame then. I don't know of any works where Death really triumphs over Fame. That's the whole point. It triumphs over vanity and everything worldly including money and position, of course, but the things we are talking about are not "vanity". And it is not particularly humanist to think so. They are the reward of virtuous conduct (even in arms) - that is the meaning of Fame here, not vainglory, *real* glory, earned and eternal.

Okay, and yes. If you think it is equivocation to deny a sharp distinction between "Renaissance" and "Middle Ages" sensibilities however, then I think you are being misled by some old books.

You have to judge it on a case-by-case basis.

Sorry, I'm not sure we got anywhere here, I didn't even get to the tarot part.

I'm fading. Read charitably.

Best regards,

Ross

(it's late for me, as you know, but hell it's Friday night... I'll do my best)

mjhurst said:So we should read it literally and presume that they were promoting heresy in their chapel?I don't see any "Judgment" in the Triumph of Death. If read literally, every soul goes to heaven, pretty directly.

No, but approach my initial statement both literally and charitably. I said "if read", not "must be read". We're reading the images from roughly the same vantage point, so I assume we're sharing impressions rather than imparting dogma.

[/QUOTE]

Or should we accept, as we do with most works, that it is not a 20,000 word treatise by a Scholastic theologian but a work of art, and that some things are taken for granted?[/QUOTE]

A lot of things can be taken for granted. I think we're just learning what they might have been. Wegener was probably the first to write down that a Wheel of Fortune was implied in the arrangement of the vignettes above Fame. Can you assume, with full confidence, that it was the obvious interpretation to everyone in 1490?

It appears that a very simple graphic design was desired here; at least, that was the result so it makes sense that it was intended.

On "paper" it looks good, and your presentation is convincing. But I haven't stood there, where it would really make a difference. Maybe the average viewer doesn't get to see much of that, and instead has to make due with the bald Triumphs, and the suggestion of mysterious things in the heavens. Even more important than the content was the use of the image. The Triumphs were the primary meaning of the images - they are the closest to the viewer.

I don't know the layout of the chapel so I'm not even sure if the left-right dichotomy works - it could be that you walk into the chapel and see Death first, then Fame. You don't stand eye-level to both and read them as a text. If you *must* pass by Death first, then Fame, then this kind of reading breaks down. It could be that they are not meant to be read the way you are reading them - they might be "stand alone" triumphs, each self-sufficient.

[/QUOTE]

Yes, there are other things that could have been included, as always, including a hellmouth or whatever it is that would satisfy you. Yes, if you were creating a similar work then you would no doubt do it differently.[/QUOTE]

I sure didn't say that. I don't even know how to conceive, in this context, of "creating a similar work". I don't much about it, including the conditions of the commission.

If you want to pursue such a line of inquiry, insisting on heresy

"Insisting"? I think you're fighting shadows here, or at least misreading (deliberately?) me. I certainly never meant to imply that *I* believed in such an interpretation, and nowhere have I insisted on it. Talk about seizing on a stray (and hoping to be somewhat funny) remark. I'll be wiser in future and keep my erudite humor to myself.

rather than artistic sensibility, that's fine. Is this heresy related to the fact that, in the other painting, the family has their backs turned toward Mary and Jesus? Gosh, this could get fun in a hurry! However, even if we accept that the Chapel was intended to convey assorted heresies, the top part of the Triumph of Death is still a portrayal of Christian end times and, in this context, (i.e., sorting out the overall cycle), the heresy is largely irrelevant to seeing the big picture.

Well, that was fun. I never thought of all that heresy. Let's see what else there is to get to.

Certainly Boccaccio's Visione is rather like Petrarch's finished product, in that glory is ultimately triumphed over by Fortune and Death, themselves triumphed by higher personifications. But Petrarch himself wrote the Triumphs of Death and Fame as the end of his work, apparently considering the four triumphs to constitute a complete and unified work. It was only two decades later, as his own mortality became a reality to him, that he changed the design of his poems to a humbler overriding arc by adding Time and Eternity.

Okay, but I imagine our 15th century readers considered it a unified work. Do you know differently? At least, all those cassoni and illustrated versions do have all six triumphs, even when they choose to emphasize some and neglect others.

Given that most of the Triumph of Fame examples we've seen are portrayed in a Petrarchian context, naturally the cyclic implication is the Christian one of the full six triumphs, always implied even if not expressed. But you seem to be suggesting that humanism did not exist, that pride in the magnificence of man and his achievements was no different than medieval Christian contemptu mundi. Since I'm pretty sure that's not what you mean, I don't know what you do mean.

I'm not really sure I understand what you're saying here. The world didn't go from medieval to "Renaissance" in 1450 (or whenever). Humanism was a multifaceted movement. There weren't many who would elevate worldly Man to the status of God. Even the most infamous humanist Prince, Sigismondo Malatesta, is shown kneeling before his namesake St. Sigismondo in his chapel in Rimini. He doesn't give himself a halo.

But... yeah, I think that the medieval Christian contemptu mundi still persisted pretty strongly, and that it's not a case of either/or.

However, you asked for an example... what is there about Lorenzo's birth tray that conveys a disdain for Gloria Mundi? Or is it a celebration of Fame?

It's obviously a celebration of Fame. For heaven's sake, look at the occasion - the birth of the first son. You want a Triumph of Death or some kind of contemptu mundi imagery, even a Wheel of Fortune, there?

This image is fully within the traditions of the society that produced it, and was immersed in the tragedy of history. If you look at other birth trays, they always have stories of great deeds and heroes (I just looked, a nice one of David and Goliath, with no contemptu mundi - definitely a humanist triumph).

We are talking about two different subjects, using the same words. Yes, Fame triumphs over Death, and yes, Death triumphs over Fame. Death means much the same thing in both formulations, but Fame differs dramatically. Artists expressed both formulations in different works.

We have to agree on the definition of Fame then. I don't know of any works where Death really triumphs over Fame. That's the whole point. It triumphs over vanity and everything worldly including money and position, of course, but the things we are talking about are not "vanity". And it is not particularly humanist to think so. They are the reward of virtuous conduct (even in arms) - that is the meaning of Fame here, not vainglory, *real* glory, earned and eternal.

Both meanings are sensible. Fame triumphs Death, and Death triumphs Fame. The question is, which is being depicted in a particular work of art. Of course, if we confuse them, using the term "Fame" ambiguously, we can generate a paradox. (More precisely, it is a fallacy of ambiguity/equivocation.) This is good too, and an artist can use that as well. But overall, I think that Renaissance humanism is a real sensibility, and the idea of worldly renown within that sensibility was quite different than it was in the more common (even during the Renaissance) contemptu mundi sensibility.

Okay, and yes. If you think it is equivocation to deny a sharp distinction between "Renaissance" and "Middle Ages" sensibilities however, then I think you are being misled by some old books.

You have to judge it on a case-by-case basis.

Sorry, I'm not sure we got anywhere here, I didn't even get to the tarot part.

I'm fading. Read charitably.

Best regards,

Ross