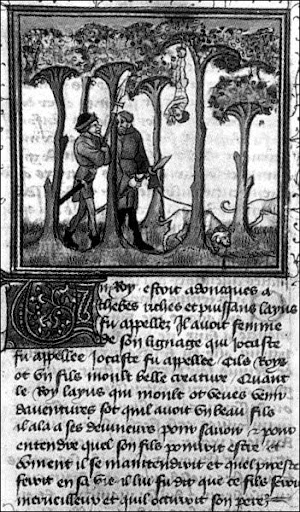

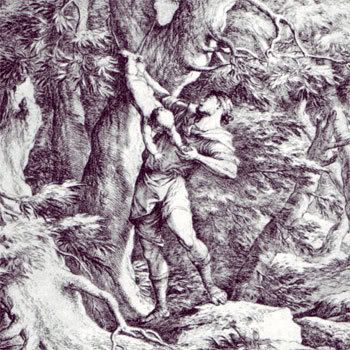

Our urge as historians is always to "read" iconography in terms of historical events, as though they happened against a "background" that stimulated their production. At this date in Paris, newborn children were still being abandoned in less flamboyant ways. There were rumors rife in the capital of a variety of Oedipal secrets at the French court; for instance whispers that Louis was in fact the lover of his elder brother's wife and actual father to the dauphin Charles. It is clearly easier to posit a point of view for Remiet's patron, Louis d'Orleans, than for the illuminator of his books. Partly because the historical and visual record of Louis as an "important" character in the constructed drama of history, carved painted, and represented in numerous effigies, there is so much more to imagine him doing with his books and images, whereas Remiet remains, like the scene-painter or the set-designer of history, somewhere offstage. I am more interested in how and why Remiet put such images together and allowed them to resonate, not only with the world outside the book but with other books, other images.

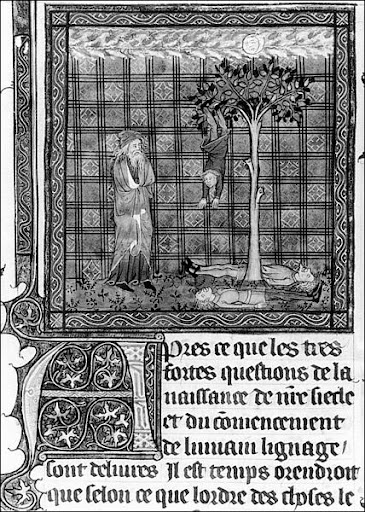

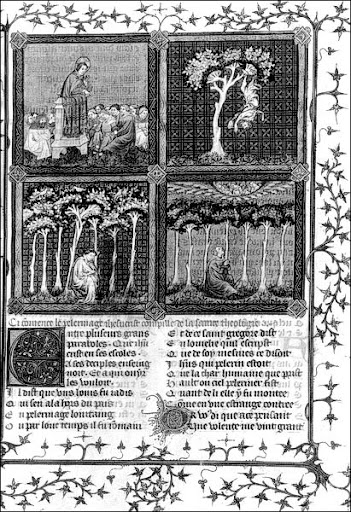

An image then can have very different meanings for a patron than it might have for its maker and rather than always seeking to place "iconography" as an intentional blueprint on meaning in the mind of the artist, which is then conveyed to the viewer/patron, as though by some direct relay, we should see many more circumlocutions in the circuits between conception, construction, and reception. Remiet was making death out of pieces of his modelbook vocabulary, pieces that no patron could know in their isolated position as fragments and yet which can be combined to form a pictorial universe. The Cite de Dieu miniature thus appears not as Remiet's unique exegetical "reading" of the text but as something far less original and thus much more interesting. Rather than a new interpretation, it is more an amalgam of current visual ideas and associations stimulated by the numbing repetitions practiced in the illuminator's workshop, the tracings and copyings, modelbooks and pricked-pounced pages, that allowed trees and falling figures and the like to be reconstituted in different contexts.