Cerulean

Etteilla 1750-91 and card Variants - background

http://www.tarotpassages.com/mkgtimeline.htm

From Mary Greer's Timeline...and to be amended with Etteilla card types as per known histories.

. 1750 Manuscript (discovered by Franco Pratesi in the late 1980s), that lists cartomantic interpretations for 35 Bolognese tarocchi cards along with a rudimentary method of laying them out. A sheet of 35 Bolognese cards (trumps and number cards) are labeled with simple divinatory meanings such as “journey,” “betrayal,” “married man,” “love.” A later deck of double-headed Bolognese cards from the 1820’s are labeled both top and bottom with divinatory meanings, showing a continuity of use.

c. 1750 Etteilla stated that he learned the art of telling fortunes with playing cards from three cartomancers, one of whom hailed from Piedmont in northern Italy. In 1757 his Piedmontese teacher led him to the tarot, declaring that these cards contained the secrets of all the wisdom of the ancients. [Huson, The True Tarot, recently republished as Mystical Origins of the Tarot].

1751-1753 Three persons in Paris were publicly known as offering their services for divination by playing cards. The practice spread until a cry of sacrilege was raised and was stopped by officialdom. [p 160 W. H. Willshire. 1876. A descriptive catalogue of playing and other cards in the British Museum. (reprinted 1975 by Emmering, Amsterdam)]

1757 Etteilla claimed that his Piedmontese (Italian) teacher first taught him the Tarot in this year.

1760 Nicolas Conver’s Tarot de Marseille-style cards engraved and printed. (Reproduced by House of Camoin in the 1968.)

1765 According to Casanova, his Russian peasant mistress would read the cards every day—laying them out in a square of twenty-five cards.

1770 Jean-Baptiste Alliette (1738-1791 publishes the first treatise on fortune-telling with playing cards: Etteilla, ou maniere de se ré cré r avec un jeu de cartes part M*** (Etteilla, or a Way to Entertain Oneself with a Pack of Cards by Mr***) which includes reversed meanings for the 32 cards. He mentions les Taraux in a list of methods of fortune-telling [Wicked Pack, p. 83].

According to Etteilla “the Book of Thoth had been engraved for posterity by seventeen Hermetic adepts, priests of Thoth, on plates of gold 171 years after the Great Flood, and that these plates had been the prototypes for tarot cards. [Huson, The True Tarot (recently republished as Mystical Origins of the Tarot.]

1770 Krata Repoa or "Initiations into the ancient society of Egyptian priests," published in German (by Von Köppen) as a revelation of a new branch of Freemasonry. Its rituals were clearly based on translations of Graeco-Egyptian texts. (See MP Hall Freemasonry of the Ancient Egyptians.) A later edition appeared in French in 1778. Dr. John Yarker published the first English edition in a Masonic Journal, The Kneph. Blavatsky claimed it was based on The Ritual of Initiations by Humberto Malhandrini, published in Venice in 1657.

1770 In the spring of 1770, the young Goethe, at this time 20 years of age, went to Strasburg in the Alsace to continue his studies at the university. There he witnessed and himself had a reading of the playing cards by an old woman.

1771 Count Cagliostro (1743-95) appears in London and Paris with his Egyptian Masonic Rite.

1776 American Declaration of Independence and beginning of the American Revolution.

1777 Cagliostro is said to have invented his scheme" of Egyptian Masonry, which would become known as the Egyptian Rite of Freemasonry (see 1782). He claims to have discovered a mysterious document in a London bookstall, written by a "George Cofton."

1778 Volume 5 of Antoine Court de Gébelin’s Le Monde Primitif contains an “Etymological Dictionary of the French Language” in which the old-fashioned form of the word, Tarraux, is listed as a “Game of cards well known in Germany, Italy and Switzerland. It is an Egyptian game, as we shall demonstrate one day; its name is composed of two Oriental words, Tar and Rha, Rho, which mean ‘royal road.’”

1781 The American Revolution ends October 19th. Uranus, first planet to be discovered since Babylonian prehistory, identified March 31 by William Herschel. Russia’s Catherine the Great and Holy Roman Emperor Josef II spilt the Balkans. Los Angeles is founded in California by Spanish settlers. Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason and Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Mozart is composing.”

1781 8th volume of Le Monde Primitif by Court de Gébelin, claiming Egyptian origin of Tarot, as a book of wisdom. Includes an essay by le Comte de M*** [Mellet] which explains how to use the cards for divination. De Gébelin says there are 22 Trumps just as there are 22 Hebrew letters. Le Comte de Mellet gives only the following correspondences (based on the cards running in a descending order): The Sun = Gimel (signifying "recompense or happiness"); The Devil = Zain ("inconstancy, error or crime"); Death = Teth ("the action of sweeping"); Fortune = Lamed ("law or science"); The Fool = Tau . We can assume that The World = Aleph, Judgment = Beth, etc. De Mellet also uses these significances for divinatory purposes. It is de Mellet also who first changes coins to "talismans" (pantacles) which is later developed by Éliphas Lévi.

According to Court de Gébelin the cards were:

0 - Le Fou

I - Le Joueur de Gobelets (Thimble-rigger), ou Bateleur (Juggler, Montebank)

Chefs Temporels & Spirituels de la Société

II - Roi

III - Reine

IV - Grand Prêtre (Chef des Hiérophantes)

V - Grande Prêtresse

VI - Le Mariage

VII - Osiris Triomphant

Planche V. No. VIII, XI, XII, XIIII: Les quatre VERTUS Cardinales

XI - La Force [coming to the aid of Prudence. Moakley]

XIIII - La Tempérance.

VIII - La Justice

XII - La Prudence

IX - Le Sage ou le Chercheur de la Vérité & du Juste. [Seeking Justice. Moakley]

XIX - Le Soleil

XVIII - La Lune (Tears of Isis). Creation of the Moon & Terrestrial Animals

XVII - La Canicule (Dog-star) Sirius (Sothis). Creation of the Stars & Fishes

XIII - La Mort

XV - Typhon

XVI - Maison-Dieu, ou Château de Plutus. [House of God overturned, with man and woman precipitated from the earthly Paradise. Moakley]

X - La Roue de Fortune

Planche VIII:

XX - Le Jugement Dernier (Last Judgment) ou La Création

X - Le Tems ou le Monde, représenreroit le Globe de la Terre & ses révolutions. [Moakley says “The Word”]

1782 Etteilla applies to the Royal censor to publish Cartonomanie Egiptienne, ou interpré taton de 78 hieroglipes qui sont sur les cartes nommé es Tarots (Egyptian Cartonomania, or Interpretation of the 78 hieroglyphs which are on the cards called Tarots). He is refused.

1782 Cagliostro founds his Egyptian Rite Lodge combined with a private temple of Isis at which Cagliostro is High Priest. His researches consist of a body of knowledge known as the Arcana Arcanorum, or A. A., and basing his "internal alchemy” on Tantrik techniques from German Rosicrucian lodges.

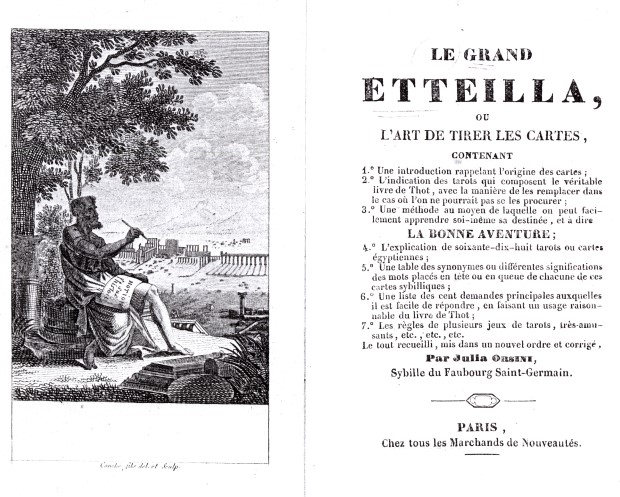

1783-86 Publication of Etteilla’s Manière de se ré créer avec le Jeu de Cartes nommées Tarots (A way to entertain onesel with the pack of cards called Tarots) in four parts. He claims it was devised by a committee of seventeen magi, presided over by Hermes Trismegistus nearly 4,000 years before. The first copy was inscribed on leaves of gold which were disposed about a fire temple at Memphis. [3Ds, pp. 83-85] His recreation of the deck has the first 12 cards based on the creation myths in the Divine Pymander, and on astrology, as he felt Tarot could be consulted in an astrological manner.

1789 Publication of the first Etteilla deck. Available as the Grand Etteilla deck from Grimaud since 1982. The Trumps and all astrological correspondences are as follows:

1 - Etteilla - Le Consultant (Male). Aries. (Papus says this is "special to the Tarot of Etteilla" - I'd make it the Bateleur (as does Edmond))

2 - Eclaircissement (Enlightenment/Fire). Taurus. (Papus: Sun)

3 - Propos (Discussion/Water). Gemini. (Papus: Moon)

4 - Dépouillement (Loss/Air). Cancer. (Papus: Star)

5 - Voyage (Travel/Earth). Leo. (Papus: World)

6 - Nuit (Night/Day). Virgo. (Papus: Empress - I'd make it the Popess)

7 - Appui (Support/Protection). Libra. (Papus: Emperor)

8 - Etteilla - Le Consultante (Female). Scorpio. (Papus: Popess - I'd make it the Empress)

9 - La Justice (Justice/Jurist). Sagittarius. (Papus: Justice)

10 - La Tempérance (Temperance/Priest). Capricorn. (Papus: Temperance)

11 - La Force (Strength/Monarch). Aquarius. (Papus: Force, i.e., Strength)

12 - La Prudence (Prudence/The Masses). Pisces. (Papus: Hanged Man)

13 - Mariage (Marriage/Union). (Papus: Lovers)

14 - Force Majeure (Absolute Necessity/Absolute Necessity). (Papus: Devil)

15 - Maladie (Illness/Illness). (Papus: Bateleur - I'd make it the Pope - it shows the same person as performed the Marriage (in bishop's fish-hat) holding a wand over an altar table with ram's heads on the corners; one of the reversed meanings is "Mage".

16 - Jugement (Judgment/Judgment). (Papus: Judgment)

17 - Mortalité (Death/Nothingness). (Papus: Death)

18 - Traître (Traitor/Traitor). (Papus: Hermit)

19 - Détresse or Misere (Poverty/Prison). (Papus: Tower)

20 - Fortune (Fortune/Raise). (Papus: Wheel of Fortune)

21 - Dissension (Disagreement/Disagreement). (Papus: Chariot)

68 - Ten of Coins = Part of Fortune

69 - Nine of Coins = South Node

70 - Eight of Coins = North Node

71 - Seven of Coins = Saturn

72 - Six of Coins = Jupiter

73 - Five of Coins = Mars

74 - Four of Coins = Moon

75 - Three of Coins = Venus

76 - Two of Coins = Mercury

77 - Ace of Coins = Sun

1789 Cagliostro arrested in Rome and condemned to death as a heretic (the sentence is commuted and he dies in prison in 1795).

1789 Beginning of the French Revolution. Storming of the Bastille - 14 July.

1791

http://www.tarotpassages.com/mkgtimeline.htm

From Mary Greer's Timeline...and to be amended with Etteilla card types as per known histories.

. 1750 Manuscript (discovered by Franco Pratesi in the late 1980s), that lists cartomantic interpretations for 35 Bolognese tarocchi cards along with a rudimentary method of laying them out. A sheet of 35 Bolognese cards (trumps and number cards) are labeled with simple divinatory meanings such as “journey,” “betrayal,” “married man,” “love.” A later deck of double-headed Bolognese cards from the 1820’s are labeled both top and bottom with divinatory meanings, showing a continuity of use.

c. 1750 Etteilla stated that he learned the art of telling fortunes with playing cards from three cartomancers, one of whom hailed from Piedmont in northern Italy. In 1757 his Piedmontese teacher led him to the tarot, declaring that these cards contained the secrets of all the wisdom of the ancients. [Huson, The True Tarot, recently republished as Mystical Origins of the Tarot].

1751-1753 Three persons in Paris were publicly known as offering their services for divination by playing cards. The practice spread until a cry of sacrilege was raised and was stopped by officialdom. [p 160 W. H. Willshire. 1876. A descriptive catalogue of playing and other cards in the British Museum. (reprinted 1975 by Emmering, Amsterdam)]

1757 Etteilla claimed that his Piedmontese (Italian) teacher first taught him the Tarot in this year.

1760 Nicolas Conver’s Tarot de Marseille-style cards engraved and printed. (Reproduced by House of Camoin in the 1968.)

1765 According to Casanova, his Russian peasant mistress would read the cards every day—laying them out in a square of twenty-five cards.

1770 Jean-Baptiste Alliette (1738-1791 publishes the first treatise on fortune-telling with playing cards: Etteilla, ou maniere de se ré cré r avec un jeu de cartes part M*** (Etteilla, or a Way to Entertain Oneself with a Pack of Cards by Mr***) which includes reversed meanings for the 32 cards. He mentions les Taraux in a list of methods of fortune-telling [Wicked Pack, p. 83].

According to Etteilla “the Book of Thoth had been engraved for posterity by seventeen Hermetic adepts, priests of Thoth, on plates of gold 171 years after the Great Flood, and that these plates had been the prototypes for tarot cards. [Huson, The True Tarot (recently republished as Mystical Origins of the Tarot.]

1770 Krata Repoa or "Initiations into the ancient society of Egyptian priests," published in German (by Von Köppen) as a revelation of a new branch of Freemasonry. Its rituals were clearly based on translations of Graeco-Egyptian texts. (See MP Hall Freemasonry of the Ancient Egyptians.) A later edition appeared in French in 1778. Dr. John Yarker published the first English edition in a Masonic Journal, The Kneph. Blavatsky claimed it was based on The Ritual of Initiations by Humberto Malhandrini, published in Venice in 1657.

1770 In the spring of 1770, the young Goethe, at this time 20 years of age, went to Strasburg in the Alsace to continue his studies at the university. There he witnessed and himself had a reading of the playing cards by an old woman.

1771 Count Cagliostro (1743-95) appears in London and Paris with his Egyptian Masonic Rite.

1776 American Declaration of Independence and beginning of the American Revolution.

1777 Cagliostro is said to have invented his scheme" of Egyptian Masonry, which would become known as the Egyptian Rite of Freemasonry (see 1782). He claims to have discovered a mysterious document in a London bookstall, written by a "George Cofton."

1778 Volume 5 of Antoine Court de Gébelin’s Le Monde Primitif contains an “Etymological Dictionary of the French Language” in which the old-fashioned form of the word, Tarraux, is listed as a “Game of cards well known in Germany, Italy and Switzerland. It is an Egyptian game, as we shall demonstrate one day; its name is composed of two Oriental words, Tar and Rha, Rho, which mean ‘royal road.’”

1781 The American Revolution ends October 19th. Uranus, first planet to be discovered since Babylonian prehistory, identified March 31 by William Herschel. Russia’s Catherine the Great and Holy Roman Emperor Josef II spilt the Balkans. Los Angeles is founded in California by Spanish settlers. Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason and Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Mozart is composing.”

1781 8th volume of Le Monde Primitif by Court de Gébelin, claiming Egyptian origin of Tarot, as a book of wisdom. Includes an essay by le Comte de M*** [Mellet] which explains how to use the cards for divination. De Gébelin says there are 22 Trumps just as there are 22 Hebrew letters. Le Comte de Mellet gives only the following correspondences (based on the cards running in a descending order): The Sun = Gimel (signifying "recompense or happiness"); The Devil = Zain ("inconstancy, error or crime"); Death = Teth ("the action of sweeping"); Fortune = Lamed ("law or science"); The Fool = Tau . We can assume that The World = Aleph, Judgment = Beth, etc. De Mellet also uses these significances for divinatory purposes. It is de Mellet also who first changes coins to "talismans" (pantacles) which is later developed by Éliphas Lévi.

According to Court de Gébelin the cards were:

0 - Le Fou

I - Le Joueur de Gobelets (Thimble-rigger), ou Bateleur (Juggler, Montebank)

Chefs Temporels & Spirituels de la Société

II - Roi

III - Reine

IV - Grand Prêtre (Chef des Hiérophantes)

V - Grande Prêtresse

VI - Le Mariage

VII - Osiris Triomphant

Planche V. No. VIII, XI, XII, XIIII: Les quatre VERTUS Cardinales

XI - La Force [coming to the aid of Prudence. Moakley]

XIIII - La Tempérance.

VIII - La Justice

XII - La Prudence

IX - Le Sage ou le Chercheur de la Vérité & du Juste. [Seeking Justice. Moakley]

XIX - Le Soleil

XVIII - La Lune (Tears of Isis). Creation of the Moon & Terrestrial Animals

XVII - La Canicule (Dog-star) Sirius (Sothis). Creation of the Stars & Fishes

XIII - La Mort

XV - Typhon

XVI - Maison-Dieu, ou Château de Plutus. [House of God overturned, with man and woman precipitated from the earthly Paradise. Moakley]

X - La Roue de Fortune

Planche VIII:

XX - Le Jugement Dernier (Last Judgment) ou La Création

X - Le Tems ou le Monde, représenreroit le Globe de la Terre & ses révolutions. [Moakley says “The Word”]

1782 Etteilla applies to the Royal censor to publish Cartonomanie Egiptienne, ou interpré taton de 78 hieroglipes qui sont sur les cartes nommé es Tarots (Egyptian Cartonomania, or Interpretation of the 78 hieroglyphs which are on the cards called Tarots). He is refused.

1782 Cagliostro founds his Egyptian Rite Lodge combined with a private temple of Isis at which Cagliostro is High Priest. His researches consist of a body of knowledge known as the Arcana Arcanorum, or A. A., and basing his "internal alchemy” on Tantrik techniques from German Rosicrucian lodges.

1783-86 Publication of Etteilla’s Manière de se ré créer avec le Jeu de Cartes nommées Tarots (A way to entertain onesel with the pack of cards called Tarots) in four parts. He claims it was devised by a committee of seventeen magi, presided over by Hermes Trismegistus nearly 4,000 years before. The first copy was inscribed on leaves of gold which were disposed about a fire temple at Memphis. [3Ds, pp. 83-85] His recreation of the deck has the first 12 cards based on the creation myths in the Divine Pymander, and on astrology, as he felt Tarot could be consulted in an astrological manner.

1789 Publication of the first Etteilla deck. Available as the Grand Etteilla deck from Grimaud since 1982. The Trumps and all astrological correspondences are as follows:

1 - Etteilla - Le Consultant (Male). Aries. (Papus says this is "special to the Tarot of Etteilla" - I'd make it the Bateleur (as does Edmond))

2 - Eclaircissement (Enlightenment/Fire). Taurus. (Papus: Sun)

3 - Propos (Discussion/Water). Gemini. (Papus: Moon)

4 - Dépouillement (Loss/Air). Cancer. (Papus: Star)

5 - Voyage (Travel/Earth). Leo. (Papus: World)

6 - Nuit (Night/Day). Virgo. (Papus: Empress - I'd make it the Popess)

7 - Appui (Support/Protection). Libra. (Papus: Emperor)

8 - Etteilla - Le Consultante (Female). Scorpio. (Papus: Popess - I'd make it the Empress)

9 - La Justice (Justice/Jurist). Sagittarius. (Papus: Justice)

10 - La Tempérance (Temperance/Priest). Capricorn. (Papus: Temperance)

11 - La Force (Strength/Monarch). Aquarius. (Papus: Force, i.e., Strength)

12 - La Prudence (Prudence/The Masses). Pisces. (Papus: Hanged Man)

13 - Mariage (Marriage/Union). (Papus: Lovers)

14 - Force Majeure (Absolute Necessity/Absolute Necessity). (Papus: Devil)

15 - Maladie (Illness/Illness). (Papus: Bateleur - I'd make it the Pope - it shows the same person as performed the Marriage (in bishop's fish-hat) holding a wand over an altar table with ram's heads on the corners; one of the reversed meanings is "Mage".

16 - Jugement (Judgment/Judgment). (Papus: Judgment)

17 - Mortalité (Death/Nothingness). (Papus: Death)

18 - Traître (Traitor/Traitor). (Papus: Hermit)

19 - Détresse or Misere (Poverty/Prison). (Papus: Tower)

20 - Fortune (Fortune/Raise). (Papus: Wheel of Fortune)

21 - Dissension (Disagreement/Disagreement). (Papus: Chariot)

68 - Ten of Coins = Part of Fortune

69 - Nine of Coins = South Node

70 - Eight of Coins = North Node

71 - Seven of Coins = Saturn

72 - Six of Coins = Jupiter

73 - Five of Coins = Mars

74 - Four of Coins = Moon

75 - Three of Coins = Venus

76 - Two of Coins = Mercury

77 - Ace of Coins = Sun

1789 Cagliostro arrested in Rome and condemned to death as a heretic (the sentence is commuted and he dies in prison in 1795).

1789 Beginning of the French Revolution. Storming of the Bastille - 14 July.

1791