Ross G Caldwell

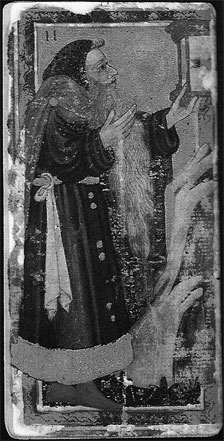

The three oldest known handpainted cards depicting the Hermit (for the sake of convenience we'll call him that) show him holding an hourglass.

He is not represented as such in any printed cards that I can recall, the three traditions showing an allegorical figure of Time with wings and crutches (A or Southern), or holding a lantern (B (Ferrara) and C (TdM)). Maybe the hourglass is added somewhere in the picture, but he is not holding it.

The allegory of Time with wings and crutches (showing Time flies, as well as the effects of age) is first attested in the early 1440s, with the earliest dated example being 1442, according to a paper by Simona Cohen, "The early Renaissance personfication of Time and changing concepts of Temporality" (Renaissance Studies vol. 14 no. 3 (2000) pp. 301-328). This personification occurs in manuscript illustrations and cassoni (wedding chest) paintings of Petrarch's Trionfi, and of course in the A or Southern kind of tarot cards.

Cohen says about the hourglass motif -

The two emphases in the quote above would seem to support, first, the idea that we cannot date the Charles VI and Catania packs earlier than 1450; second, it reinforces what we know about Dominican and Franciscan preaching about the sins of playing games, which in the 1440s and 1450s was listing them starting with "Amissio temporis" - wasting time.

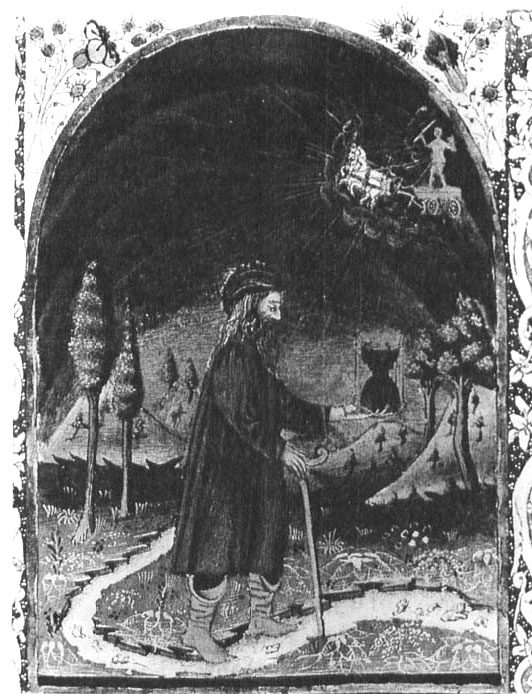

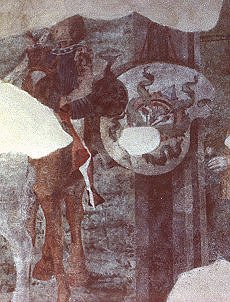

Cohen provides many examples of the Triumph of Time, but one she shows is the closest cognate image I have seen to the earliest tarot images -

Cohen simply describes the image as "North Italian illumination, 1459", with its location in the Österriechische Nationalbibliothek, Vind. 2649, fol. 46r.

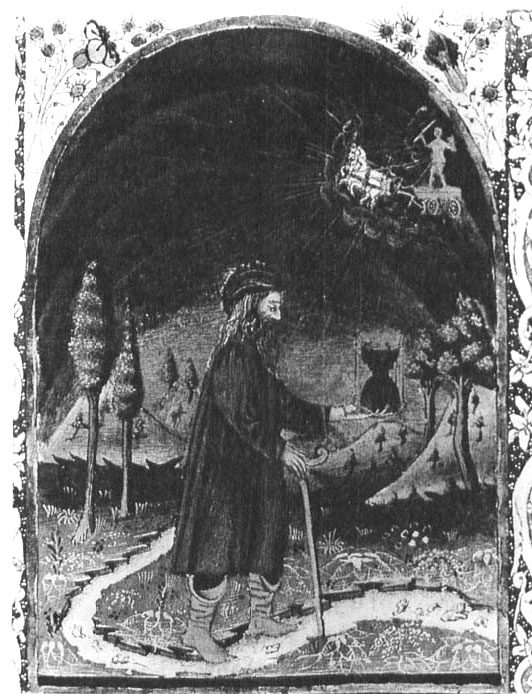

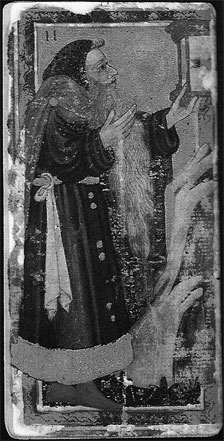

Comparing it to the set of related tarot cards:

I couldn't find a better image of the manuscript, but another author made an allusion to the work and gave some other details. Enrico Maria dal Pozzolo, "Laura tra Polia e Berenice di Lorenzo Lotto" (Artibus et historiae, 13, no. 25 (1992) pp. 103-127), informs us that ms. 2649 of the ÖNB was "illuminated in Pesaro by Giovanni da Verona in 1459", and JB Trapp ("Illuminations of Petrarch's Trionfi from Manuscript to Print and Print to Manuscript") adds the detail that the manuscript was made for Borso d'Este (p. 242; but calls the artist "Giacomo da Verona").

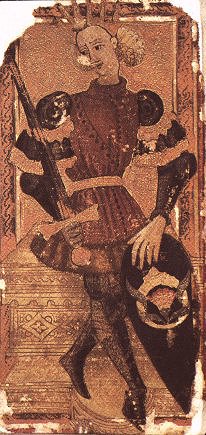

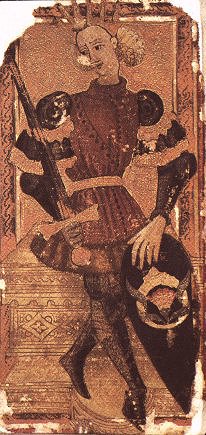

Assuming that Dal Pozzolo's information is correct that the manuscript was made in Pesaro, an interesting coincidence results - the Catania deck is more commonly known as the "Alessandro Sforza" tarot, because his heraldic emblem is on the shield of the King of Swords -

(compare to another instance of the same device -

in Carpi)

What is coincidental is that Alessandro Sforza was Lord of Pesaro from 1445-1473, containing the time-frame for the composition of this tarot deck.

The Giovanni (or Giacomo) da Verona image is not an exact match to the cards, but it does show a strikingly similar approach to the allegory of time, and the presumed commissioner of the deck in Catania was Lord of the city when the image was made there, so we could be witnessing a particular fashion of a time corroborating Cohen's observation that the hourglass doesn't become a feature of the allegory until the 1450s.

Ross

He is not represented as such in any printed cards that I can recall, the three traditions showing an allegorical figure of Time with wings and crutches (A or Southern), or holding a lantern (B (Ferrara) and C (TdM)). Maybe the hourglass is added somewhere in the picture, but he is not holding it.

The allegory of Time with wings and crutches (showing Time flies, as well as the effects of age) is first attested in the early 1440s, with the earliest dated example being 1442, according to a paper by Simona Cohen, "The early Renaissance personfication of Time and changing concepts of Temporality" (Renaissance Studies vol. 14 no. 3 (2000) pp. 301-328). This personification occurs in manuscript illustrations and cassoni (wedding chest) paintings of Petrarch's Trionfi, and of course in the A or Southern kind of tarot cards.

Cohen says about the hourglass motif -

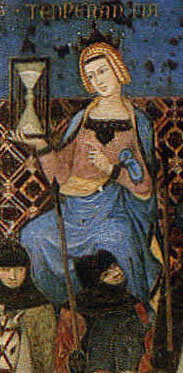

An important attribute of time, the hourglass, seems to have made its first appearance in the Trionfo del Tempo about 1450. It was then introduced in a whole series of cassone. We have seen that images of the initial stage [of depictions of the Triumph, 1440s], such as the globe and elements, were carried over by medieval cosmic imagery, but the hourglass had no cosmic connotations and was comparatively new to art: the earliest known depiction, used as an attribute of Temperance in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena, preceded its appearance in the Trionfo del Tempo by about 100 years. Temperance signified moderation, regularity, and restraint, in other words, moral self-discipline or the self-imposition of limits. The hourglass of Temperance showed that proper measurement and utilization of time was a virtue. When in the fifteenth century Time made his debut with an hourglass, Temperance had long ago forsaken hers for a clock. Although there is one example of a mechanical clock on a cassone of the mid-Quattrocento, the fact that illustrators of that period still preferred to represent time by the hourglass, rather than the modern clock that was perfecting time measurement, indicates that these were not interchangeable symbols. The regularity of clockwork had become a simile for the regularity of man's body and spirit when ruled by reason. The hourglass conveyed the idea not of accurate measurement but of the brevity of human life. It was a perfect object to express the sense of value that men attached to the brief time allotted them. Concurrent with the appearance of the hourglass in Italian art, there was new emphasis on a more practical approach to time in religious and secular literature. (pp. 311-313; bold emphasis added)

The two emphases in the quote above would seem to support, first, the idea that we cannot date the Charles VI and Catania packs earlier than 1450; second, it reinforces what we know about Dominican and Franciscan preaching about the sins of playing games, which in the 1440s and 1450s was listing them starting with "Amissio temporis" - wasting time.

Cohen provides many examples of the Triumph of Time, but one she shows is the closest cognate image I have seen to the earliest tarot images -

Cohen simply describes the image as "North Italian illumination, 1459", with its location in the Österriechische Nationalbibliothek, Vind. 2649, fol. 46r.

Comparing it to the set of related tarot cards:

I couldn't find a better image of the manuscript, but another author made an allusion to the work and gave some other details. Enrico Maria dal Pozzolo, "Laura tra Polia e Berenice di Lorenzo Lotto" (Artibus et historiae, 13, no. 25 (1992) pp. 103-127), informs us that ms. 2649 of the ÖNB was "illuminated in Pesaro by Giovanni da Verona in 1459", and JB Trapp ("Illuminations of Petrarch's Trionfi from Manuscript to Print and Print to Manuscript") adds the detail that the manuscript was made for Borso d'Este (p. 242; but calls the artist "Giacomo da Verona").

Assuming that Dal Pozzolo's information is correct that the manuscript was made in Pesaro, an interesting coincidence results - the Catania deck is more commonly known as the "Alessandro Sforza" tarot, because his heraldic emblem is on the shield of the King of Swords -

(compare to another instance of the same device -

in Carpi)

What is coincidental is that Alessandro Sforza was Lord of Pesaro from 1445-1473, containing the time-frame for the composition of this tarot deck.

The Giovanni (or Giacomo) da Verona image is not an exact match to the cards, but it does show a strikingly similar approach to the allegory of time, and the presumed commissioner of the deck in Catania was Lord of the city when the image was made there, so we could be witnessing a particular fashion of a time corroborating Cohen's observation that the hourglass doesn't become a feature of the allegory until the 1450s.

Ross